As we continue to recognize Mobility Awareness Month, we asked our client Tracey Porreca for insights into how she has navigated an evolving relationship with mobility living with hypophosphatasia and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome among other diagnoses.

I grew up feeling different than other kids—but I didn’t know why.

While I wasn’t diagnosed until adulthood, I had many of the signs of hypophosphatasia from birth, including early tooth loss, difficulty walking due to weak bones and muscles, and headaches. I struggled to keep up with my peers and found it difficult to enjoy the activities most kids enjoy—I just wasn’t able to keep up.

Before my diagnosis, I was simply considered clumsy. I had a great deal of pain and fatigue, and I learned that I needed to pace myself, which was its own challenge because even my family did not understand why I struggled. I also experienced guilt because plans would need to change because of my fatigue or inability to do certain things.

I was diagnosed after my third child was born with a diagnosis of his own: a more severe form of my own metabolic disorder. He was 2 years old when diagnosed – I was diagnosed at the age of 30. Upon further investigation, my oldest child was also diagnosed at age 8, and subsequently. my father was diagnosed. The disorder was found to run in our family.

Since that time, we have all adapted and learned how to deal with things like fatigue, pain, and mobility. However, it’s never easy. I’m taking each day as it comes now.

My mobility challenges have been slow but progressive throughout my life.

When I was young, it was an inability to keep up with peers—but as an adult and mother, I struggled to balance marriage, motherhood, and work along with everyday needs like housekeeping. I experienced fractures and spent a lot of time using mobility aids like crutches. Eventually, I fractured my femur and spent time in a wheelchair.

I was able to move independently again, but I continued to deal with fractures and mobility barriers and used crutches, canes, walkers, and splints at different times.

In 2018, I had a total knee replacement that failed, and I ended up starting to use a wheelchair for most trips outside even though I could still walk in my own home. In June 2020, I was diagnosed with COVID-19, and the mobility downhill spiral began. I’m still dealing with the effects of COVID-19 more than two years later. In the summer of 2021, I was diagnosed with breast cancer, which led to additional health and mobility disruptions.

I have been a full-time wheelchair user for several years now.

Despite my health declines, I have always pushed myself hard. I love the outdoors and being active, and I have been able to do many things out of sheer willpower and perseverance. However, I’ve had to bow out of many activities that I desperately want to participate in because I just knew I couldn’t do them—things like hiking in the mountains in my home state of Alaska were never possible for me.

I have used every tool I can to stay active. I adopted the attitude early on that mobility aids are a source of help, not something to be embarrassed or ashamed about. If I need crutches, or a splint, or a wheelchair, I use them.

My mobility aids give me freedom, and they do not hinder me.

I remember going out into the Alaskan wilderness in my car, driving from point to point to photograph dog mushing races. I carried my crutches and other mobility aids, just in case.

There’s a financial side to mobility.

I believe anyone who, like me, has to approach things differently is going to find out that it costs them more. After all, even a choice like eating healthier comes with an increased cost.

Being able to move around in a world that is not meant for your mobility is always going to have a cost associated with it. It’s unfortunate, and it’s where the term “disability tax” comes into play: an unseen cost that people without physical disabilities do not incur.

People who don’t have mobility issues might have an advantage as they move in the world, but that advantage often comes along with many burdens put on those of us who must approach things like mobility a little differently.

Some of my mobility essentials are my wheelchair, an accessible vehicle (which I currently do not own), splints, crutches, braces, medications, and home modifications that allow me to shower and cook from my wheelchair. All of these things do not come free. Even items that are covered by insurance may be subject to co-pays and cost limits. Many other items like continence supplies are not covered, so you have to pay full price for these despite having a diagnosis that makes them medically necessary.

Travel is also a significant expense.

I live in Alaska but see a specialist once per year in Tennessee. That’s a plane ticket, a hotel stay, and costs like food while you’re there. Even my “local” doctors are 350 miles from the rural area where I live—there are no doctors closer to me.

As I became a full-time wheelchair user, I was able to get a custom wheelchair with help from my insurance that had power assist wheels to make it easier to push (and safer to use as someone who is prone to fractures). However, I’d only had the manual chair for a few years when I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2021. I had a double mastectomy, and the pain and recovery have made it very difficult to use my arms to push my wheelchair.

The bills since my cancer surgery have been overwhelming, so as I looked at portable power chairs, I realized there would be no way that I could afford it.

I was falling through the cracks—that’s why I turned to Help Hope Live.

I heard about Help Hope Live through the first virtual edition of the Abilities Expo, but I didn’t move forward with fundraising until getting that portable chair became a very real need. Help Hope Live Ambassadors Sharon and David Talkington discussed their Help Hope Live experience with me, and that helped me decide to move forward with my own campaign.

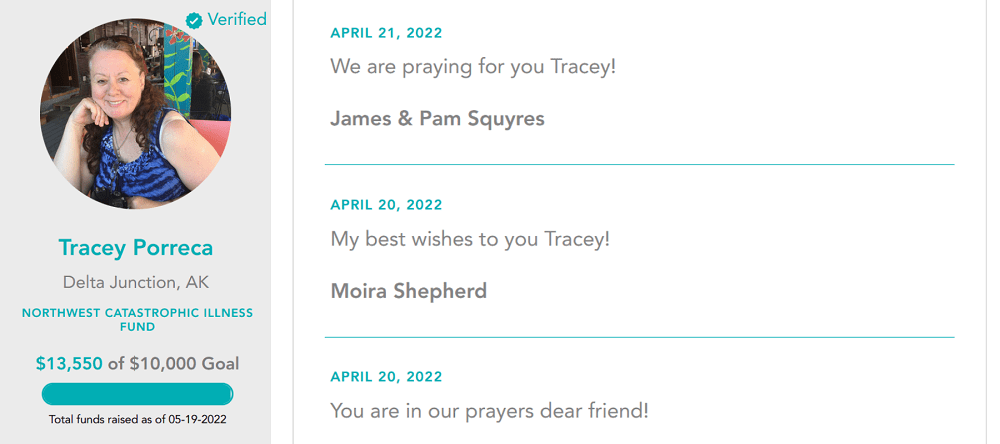

My campaign has raised over $13,500 in two months, well past my $10,000 goal.

I’ve used social media for my business, so my entire fundraising campaign was launched through social media—mainly Facebook and YouTube. We live in a very remote area, so social media was really the best way to accomplish our fundraising goals.

I still don’t have the words to express how surprised, humbled, and grateful I am. I have always been a giver, and people like me who do for others often find it difficult to ask for help themselves.

I struggled so much with this, but once I decided to move forward, my friends and community really came through.

My portable power chair is here. It’s all so new—in fact, I haven’t even had the chance to use it outside my home yet, but I am so excited by the possibilities. In my home, it has made a huge difference already: it makes it easier for me to get around; I don’t have as much arm and back pain as I did before; and I’m able to go outside where I couldn’t go with a manual chair. I can’t wait to get into my garden with my new chair.

My focus is my health and getting through the remaining treatments for cancer and other diagnoses. My husband and I have a small travel trailer, and we are really looking forward to camping this summer. Longterm, I want to write articles and books. I miss public speaking, as I really enjoy it, but I can’t keep up with the pace like I could before. I’m happy just to be able to contribute what I can in the disability community.

I have a challenge for anyone who doesn’t have a mobility issue…

For the next week, everywhere you go, look for a ramp or curb cuts—at a restaurant, at work, or at an appointment. Look at thresholds and doorway widths. If you don’t see them, ask yourself why. Ask the business why.

You’ll find that many places you access regularly are inaccessible to someone with a mobility issue. There are so many barriers that it would be impossible to list them all—we must do better.

One thing I wish everyone knew about mobility is that mobility aids are just that: aids.

They can make your life better, and they should not be looked at as giving up, being lazy, or not trying hard enough. I’m a big proponent of the “social disability” model, which says it’s our environment and public perception that are our greatest hindrance—not our physical disabilities.

Negative perceptions of disability are, in my opinion, our biggest challenge and the one thing I’d most like to see change in the future.

Disability should never be perceived as a negative word or state. It should be a term associated with a thriving community of individuals who are living life just like everyone else. They might approach things in a different way, but that doesn’t make them any less important as members of society. This truth should never be minimized or forgotten.

My hope is that one day, everyone will be able to access the things they wish they could access without having to struggle in the way that so many of us have in the past and continue to struggle today. Everyone has ownership in this conversation, and working together, we can all make a difference and make things better for everyone.

In telling my story, and in seeing others share theirs, I hope that everyone will learn and understand that we are people who just approach mobility a little differently than they do—it does not make us “less than”.

So what if I approach things differently? It takes strength and courage to live in this world.

Keep up with Tracey’s mobility, fundraising, and advocacy efforts by subscribing to her Campaign Page.

Written by Emily Progin