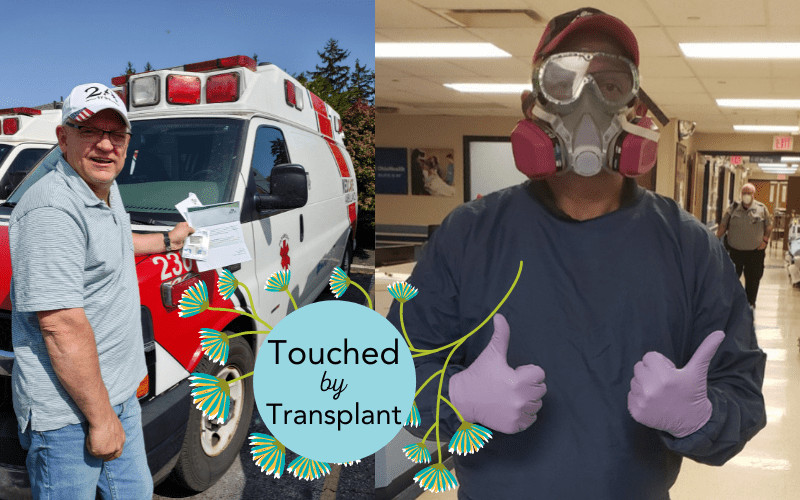

Patrick Pennington spent decades as a dedicated Emergency Medical Services (EMS) professional before lung disease and an urgent transplant need put his career on hold. These are his reflections about his work as a paramedic, what we can all learn from the COVID-19 pandemic, and why hope is a central part of his life today.

My first realization of wanting to be a paramedic was in 6th grade—mostly due to watching the show Emergency! 51 on TV. I wanted to be like Johnny and Roy:

I wanted to help people.

As a child, I thought it would be awesome to drive a fire truck. I got to slide down a fire pole when I visited the local fire station. That same child felt compelled to help family, friends, and strangers whenever called upon. As an adult, my need to help others grew even stronger.

I wanted to be the person who gave aid, compassion, and comfort in someone’s hour of distress.

My start in the EMS field was working as a supply clerk for a transport service. My job was being in charge of handing out appropriate required equipment to crews on the road—like a first responder bag, monitor, and a portable radio—according to what the crew needed. My other duty was to clean, disinfect, restock supplies, and fill the oxygen tanks for the night medics on station.

When I became a paramedic, my days would vary depending on the service and the patrons we served. As a first responder, I only replied to 911 calls. When I was performing transport service, I rendered care to patients during interfacility runs, which could be anything from the ER to a hospital that could offer a higher level of care to a patient’s doctor appointment.

The Most Rewarding Part of My Job

I worked 24 hours on shift as a 911 paramedic, then I was off for 48 hours. If we had any spare time on shift, we would eat, study, continue our educations, and sleep when possible.

While on shift, we all waited for the signal that we needed to make a run. No matter what we were doing, we stopped in our tracks and responded. When we arrived on scene, we assessed the patient and rendered medical care if needed. We might lift the patient to a cot, secure them, and lift them into the back of the ambulance. Medics also gave enroute care to patients if they needed it.

When someone experiences a medical challenge, you often know more about how they are doing through the things you notice that a loved one might not see right away. Those things you see are never forgotten, and it’s hard not to look for the same signs and symptoms in family members, friends, strangers, and enemies—you see them in everyone.

I often feel like I am a paramedic even when I’m not at work.

By far, the most rewarding part of my job was being able to help a family member, a friend, or a stranger. Sometimes, it was delivering medical care—sometimes, it was just holding their hand and talking to them on the way to the hospital.

I never looked for or expected a “thank you” from them or their family members.

My best reward was just knowing I did everything I could to help them or medically care for them.

How COVID-19 Impacted Me—and All of Us

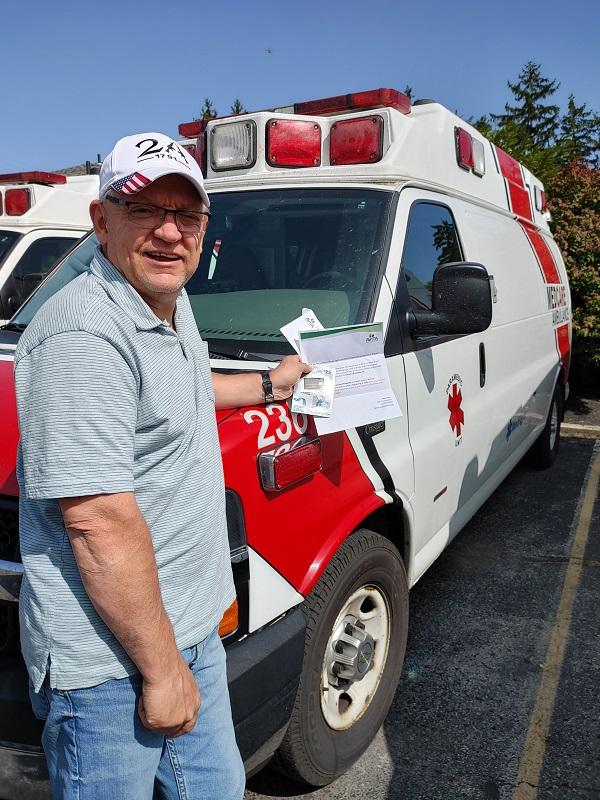

COVID-19 had a major impact on EMS workers and health care workers.

My workday was no longer a “normal” workday: I had a new uniform to wear with a mask, respirator, eyewear protection, and a face shield. We wore double layers of gowns and gloves. We had new protocols and procedures that were ever-changing from the CDC and our employer, just as fast as the COVID-19 pandemic itself changed.

Transporting patients to their destination now increased my risk of exposure, and along with it my chance of possibly spreading COVID-19 to my family members and friends. That led to me changing my entire routine when I came home, doing everything in my power to prevent the spread of infection.

The pandemic caused chaos, which then became a kind of new normal.

Never take for granted that tomorrow will come. Life can be unfair, too. Tell your family or that special person in your life that you love them.

COVID-19 was a reminder that there is no guarantee for what will happen next in life.

During the ordeal of COVID-19, I cared for and transported people who never got to say that “I love you” to their loved ones. The same day I entered the hospital to get treatment for COVID-related pneumonia, my father-in-law was hospitalized for COVID-19 at a different hospital. I was able to walk out of the hospital after a five-day stay and tell my family how much I loved them. My father-in-law did not get the same chance: he passed after 24 days in the hospital without saying, or hearing, a final “I love you”.

My Journey to the Lung Transplant Waiting List

A year before the pandemic, I had been diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. By July 2019, my testing results showed increased damage in the alveolar sacs and thickening of the tissue in my lungs.

I was already living with some scarring and thickening in my lungs, which was treated successfully with medication. I also went on a diet with exercise and lost 92 pounds, which helped tremendously with my health.

However, COVID-19 had a big impact on my lungs.

I had my first post-COVID lung scan in March 2021. Even though the scan didn’t show a significant difference, I began to notice an increased shortness of breath during exertion, and I had a cough that at times was forceful and even uncontrollable.

The symptoms worsened.

By June 2021, I was back in my pulmonologist’s office, because my symptoms were interfering with my work. Scans showed the damage to my lungs had gotten worse. There was new scarring-called “honeycombing”—and progression in my diagnosis at a rate faster than would be considered normal or expected.

That’s what sent me to the OSU Wexner lung transplant team.

Engaging My Community of Support

The response from my community was a delayed one: I initially didn’t let anyone other than my wife know about my health condition, because I hadn’t come to terms with the sudden change in my health myself. My wife and I tried to grasp the severity of the illness. We had a lot of information coming to us at once as I began the process of becoming a transplant patient.

All I focused on was the statistics indicating the percentage of transplant candidates who got a poor outcome and passed away. As a result, I wanted to know a lot more about my disease and treatment because I knew friends and loved ones would ask.

I wanted to have answers for all their questions.

I finally told my children about the diagnosis about three to four months into the transplant process. I told the rest of my family shortly after.

My kids seem to be dealing about me needing a transplant primarily by not talking about it—almost as if not talking about it means it won’t happen. But don’t get me wrong: I see them a lot more than I used to, and they are always checking in to see how I’m doing.

My mom wants to know all about what is going on with her youngest child. She is always asking me if I’m on “the list” yet.

My coworkers knew more before my family did because I hadn’t been at work, and they knew that this just was not my normal.

The Hardest Thing I’ve Ever Done

Stepping away from my work due to the changes in my health has been the hardest thing I have ever done.

I have worked in EMS for the last 28 years and as a paramedic for the last 23 years. I always went to work loving my job and what it brought with every shift.

I still have hope to returning to my career after transplant.

All I ever wanted to do was help the community that I lived in and support my neighbors. I am staying abreast with continuing education, hoping to remain proficient and keep up my knowledge and skills in paramedicine.

…And the Second Hardest

The second hardest thing I’ve ever had to do is to ask strangers to help take care of me.

I was raised to work hard, take pride in your work, and support your family—and if a stranger ever needed a shirt, you gave them yours.

For that reason, fundraising was rough for me. I don’t like asking for financial help. I have never done anything like this ever in my life, so I was really in uncharted territory.

A few months into the transplant process, I finally started a campaign with Help Hope Live.

I chose Help Hope Live initially because of the name. It says it all: I need help, and I have hope to live a better future. It says what I feel like I can’t, since I have a hard time asking for a better life.

I liked the fact that Help Hope Live took the stress away in terms of distributing the funds raised, and I liked the feedback and success stories I heard from past transplant patients.

The nonprofit came highly recommended from all I talked to.

Life Before—and After—Transplant

Waiting for “the call” feels like crawling forward in snail mode. What you have to do to get on the waiting list is in-depth and overwhelming at times—it feels like there is no stone left unturned. You keep telling yourself that the call will come at any minute.

It’s like a child, asking you “are we there yet?” repeatedly on a road trip.

I’m not sure what to expect from life after transplant. In all honesty, I’m scared! I know the outcome will be that I will be able to live a better life: I will be able to breathe better and not have shortness of breath when I exert myself, and I won’t wear out doing the smallest activity.

I know that life has no guarantee, but I plan to make the most of the extension of life that I will be given. I know I want to return to work doing the job I love and helping people in need of my care.

I want to live life for my donor’s chivalrous choice of donating life.

Why Hope is My Anchor

To me, hope is the anchor I cling to with every part of my soul.

My hope begins with someone else deciding to help a stranger in need of life. Hope is every time I decided not to give up on life when the chips were down. Hope is waiting to be put on the transplant list and waiting to receive the call. Hope is not giving up on your dreams when the light at the end of the tunnel is dim.

With hope, you have to have faith. Hebrews 11:1: Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.

This Donate Life Month, I would like the world to know that the gift of life is the greatest treasure they own. It is precious and fragile, and it is waiting to be lived.

The greatest hope for humanity to survive is that there are still people who will selflessly give of themselves to help a stranger. There is no “thank you” great enough for someone who decides to be a donor of life.

To become a part of Patrick’s journey to transplant, visit his Campaign Page. If someone you know is struggling to cover the cost of a transplant or COVID-19 recovery, our nonprofit may be able to help.

Written by Emily Progin