Jason Dorwart has been offered a position in his field of theater and disability studies in Hong Kong. In addition to relocating his wife and 3-year-old daughter overseas, he needs to raise $30,000 for a critical personal mobility device to help him navigate accessibility in a new city. This is his story.

When were you injured?

I was injured in August 2000 while swimming in the ocean in Mexico. I was tossed by a wave and hit a sandbar.

Luckily, my dad was swimming with me, and he got me out of the water. We were in a fairly small town with only a volunteer rescue squad, but thankfully, some San Diego firefighters were there on vacation and just happened to be on the beach when I was injured. They helped ensure that I got proper emergency care for my spinal cord injury.

I spent the first month in the ICU at a hospital in Pasadena, California. I was lucky to have grown up outside of Denver where Craig Hospital, one of the best spinal rehabilitation centers, is located—I spent three months in spinal cord injury rehab there.

How did the injury affect you and your community?

It was hard for my family at the time, but they were very good at not adding to my stress. The community I grew up with was very supportive and giving as my family coped with the injury.

I’m a very stubborn person, so when I was first injured, I immediately jumped into rehab, trying to figure out how to make this new life work. When I was still in the ICU, one of the nurses told me that I would be able to do everything I previously did—swim, travel, drive, hold a job, and even raise a family.

I don’t like giving up on dreams. Today, I remain determined to make my future happen, and I’m so thankful for all the support I’ve had along the way.

How did you establish your career path?

After my injury, it took me a while to figure out exactly what I wanted to do. I was studying theater in college with the idea that I would become a teacher or professor. After I became a quadriplegic, I continued to perform with a theater company in Denver called Phamaly Theatre Co. that is entirely made up of people with disabilities.

I pursued a career in education, obtaining a bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, law degree, and PhD. I became a visiting assistant professor at Oberlin College, and I’ve been in that position for the last four years teaching theater, film, and disability studies.

Only about 10% of people with PhDs ever land a tenure-track job. I’m very proud to be one of the few who have, but I also recognize that I never could have done it without community support.

Has accessibility been a barrier in your career?

I’ve encountered many obstacles related to widespread inaccessibility, many of which seemed insurmountable. I was accepted into a graduate program abroad, but the administrators called me at the last moment to let me know that they hadn’t realized I used a wheelchair all the time, and they were not able to accommodate me—their facilities were inaccessible. I couldn’t attend the program, and I had to hastily make other plans to continue my education.

Similarly, when I applied to PhD programs, I was accepted at four schools—but only one of the four was fully wheelchair accessible. I had to attend that one, not the one that offered me the most financial support or opportunities.

When did you come across the teaching position in Hong Kong?

I first saw this job advertised in August 2020. They were looking for someone to teach in the English department about global theater history with a specialization in disability studies. Despite the advice from my PhD advisors that my educational focus would be a hot commodity in the future, this was the first job I’d seen advertised as a professor of theater and disability since I graduated.

Even though I thought I was a long shot for the position when I applied, I figured I had to give it a try. I got the job—and I am so very excited!

There will be challenges in moving my wife of five years, Laura, and my three-year-old daughter, Ruth, to Hong Kong, but it’s difficult to land a stable job like this. We ultimately concluded that the opportunity was too good to pass up.

Hong Kong and China are very interested in increasing the scope of their disability studies offerings, and I’m excited to be able to be a part of that.

Hong Kong Baptist University

Is Hong Kong an accessible destination?

I had previously read that Hong Kong is a great place to travel for tourists who use wheelchairs. What I didn’t realize is that everyday life as a resident in a wheelchair is a bit harder than it is for tourists.

As I looked online at pictures of neighborhoods we might want to live in, I noticed that the city is built on a mountainside, and most businesses have at least one step (in part due to the flooding during the monsoon season). That makes it difficult to get around.

Many businesses and professional facilities have steps or stairs. These small barriers could stop me from living a normal life with my family. The daily stress of inaccessibility would take its toll—not only on me, but on my wife and eventually my daughter as well.

The university is doing what they can to provide for accessibility. The job includes housing, and the university is remodeling an apartment so that it will be accessible for me. They are also purchasing assistive technology for me. However, the funds they’re providing can’t be used to cover “personal adaptive equipment.” That’s where fundraising comes in.

What are you fundraising for to bring this position within reach?

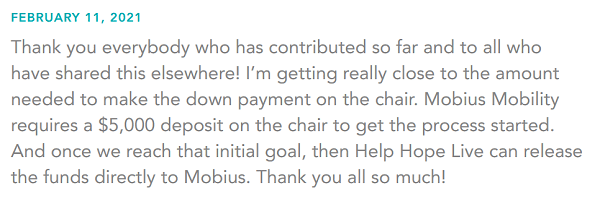

I am fundraising with Help Hope Live for the iBOT PMD (Personal Mobility Device). It is a stairclimbing wheelchair that uses technology similar to a Segway. It can go up curbs and steps and cross uneven terrain.

The cost of this wheelchair is $30,000, which is beyond my family’s current means.

Reaching this goal will allow me to pursue the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity I’ve been offered and give my family what they deserve. The wheelchair and this position will open up the world to me and my family.

What does community support mean to you as you prepare for this new opportunity?

There are so many expenses associated with spinal cord injuries and wheelchair use. The cost of an aide and mobility devices have often stalled my career and derailed my financial security. About half of my monthly pay usually went to an aide just so that I could live independently and get to work on time.

I was often hungry and struggling—because I earned slightly more than the income cap, I did not qualify for disability benefits. The fact that I have this opportunity now is the most wonderful payoff for that struggle.

Community support and help on social media is so very important to me. Knowing that there are hundreds of people who want to support this endeavor in their own small way feels really good.

I don’t think I would be able to afford all the opportunities I have today if it weren’t for community support.

What do most people misunderstand about life in a wheelchair?

I don’t like the language of being “wheelchair-bound” or “confined to a wheelchair” at all. Expressions like that assume that people in wheelchairs can’t do amazing things—and we can do similarly wonderful things when we’re not in our wheelchairs, too. A wheelchair isn’t something that we are confined to. It is a tool for independence.

What does hope mean to you?

Hope kept me going in the early days of my injury. When I felt depressed and that there was no respite in sight, I thought about hope a lot. I tried to remember that as long as I woke up tomorrow, there would always be the possibility of doing new and wonderful things.

Even if today is hard, you might just meet somebody wonderful tomorrow. If you trip up today, you might soar in the future.

Right now, my greatest hope in life is to be able to support my family financially and be fully integrated into my daughter’s academic, extracurricular, and social life and activities rather than excluded due to inaccessibility. With this new opportunity, I will be able to do so.

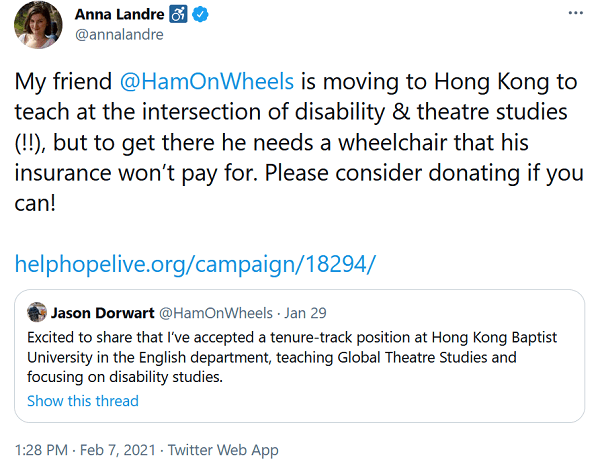

Subscribe to Jason’s fundraising journey on his Campaign Page. Follow him on Twitter @HamOnWheels.

Written by Emily Progin