Our client Kabir Kadre has been living with C5 quadriplegia since a 2003 car accident on a road trip with friends. Read his reflections on life with an SCI then and now, the power of fundraising, and the close connection between caregiving and community.

Can you paint a picture of some of the early days of your SCI journey?

Different body, different needs, different focus…different everything.

I was in extended hospitalization for three-and-a-half months. The hospital was understaffed and unable to care for the intensive requirements of my condition—as a result, I lost nearly one-third of my bodyweight due to malnourishment and neglect. During that period, I was undoubtedly experiencing emotional depression, though the condition was largely unrecognized by me at the time.

My initial focus was on challenging the prognosis and developing the greatest possibility of full recovery and return to function. We were early in the process of understanding and developing a home life that would be necessary for me to function as a quadriplegic in my “new” physical body.

Without any place to be outside of my bed, and with diminished access to communication or work technology, I remained prone or inclined for the better part of each day and week. I ventured out of bed for about five days per week, roughly six hours per day, to attend an intensive recovery therapy program.

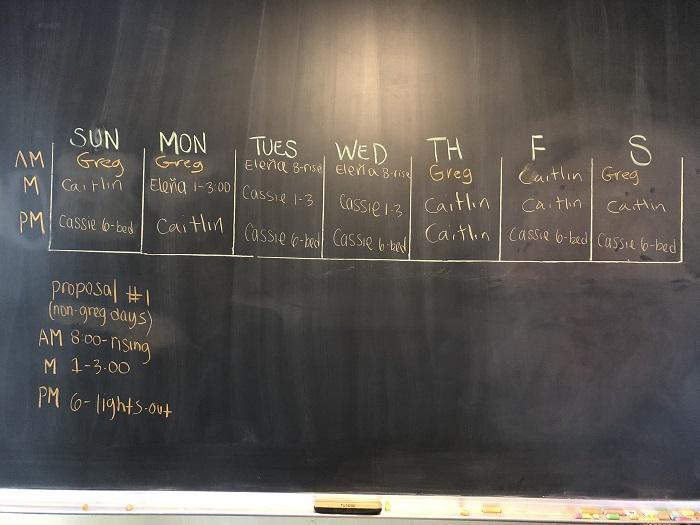

At that time, my available care consisted primarily of my brother, who lived with me, running the household in every respect and ensuring I had all of the direct care I needed. We had about 40 hours per week of hired caregiving support.

In those early days, I knew nothing of my care needs, concerns, or the trade-offs involved in my day-to-day life with an SCI. Many of my early health challenges had to do with a lack of experience or education regarding the nature of my condition and its peripheral concerns. For instance, I faced frequent urinary tract infections – it was nearly a decade later before I first learned the specifics of proper bladder management and the risks of death associated with its failure.

How does your life look different today?

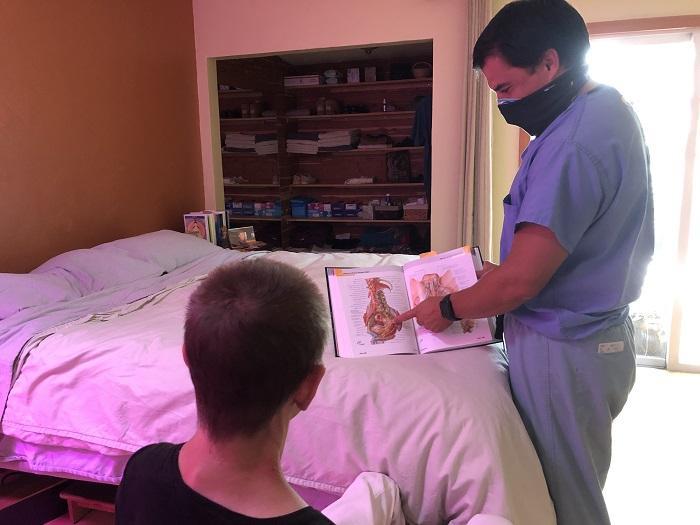

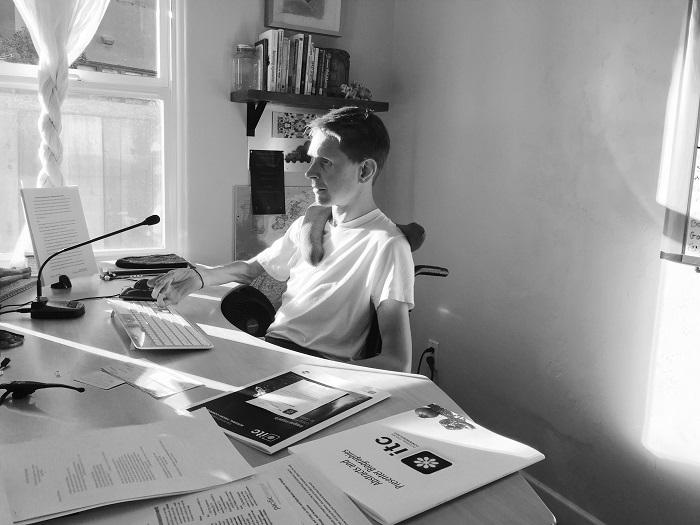

I made the move from being a disempowered director of my affairs to being an engaged leader in my life and care. Today, I am running my own household and have a care team of five people formally on payroll and additional support from nearby friends in the community. I am out of bed daily (health permitting) with full knowledge and direct management of my health care.

I have a much more sophisticated and nuanced appreciation of the nature and pace of “recovery.” The largest portion of my time now is devoted to efforts to better understand our world, seeking ways large and small to be of service within our time.

Do you face ongoing, SCI-related health challenges?

I do live with ongoing health concerns related to SCI. Autonomic dysreflexia (AD) is often the only information signal that indicates the presence of an infection, malfunction, or discomfort – without distinction for where in the body the issue is arising. As a result, I still struggle today to keep up with ongoing and emergent issues, which may range in severity from a shoe being too tight to a potentially life-threatening concern like cellulitis.

What are some of the recurring costs associated with SCI?

I have a monthly expense of about $10,000 for caregivers who help me in the physical aspects of life. I probably use another $200 per month in medical supplies, $300 per month for doctors and medical services, and $150 per month for nutrient supplementation to help me maintain my health.

Then there is the occasional expense for durable medical equipment: $3,000 for a bathroom chair, $5,000 for a wheelchair, and nickels and dimes along the way to manage accessibility concerns.

When fundraising is going well, I will spend an additional $500 to $1,500 per month for active therapeutic support that provides physical exercise and the development of a more robust physiological health foundation.

These expenses just about get me to “zero”: the best-case scenario is serving as a business manager as a way of life—every moment is spent holding together the bottom line. Accomplishing each day brings the rewards of a sense of gratitude. Staying well for one more week is a source of inspiration and joy.

That foundation slides away quickly if the business manager cannot uphold the income and managerial effort to keep things moving, and things can get very dark indeed. However, with fundamental costs covered, the sky begins to open up. With it, the heart lifts more freely, and the well-being of the body follows close behind.

To be certain, money, care, and stability are not guarantees of well-being or physical health, but they provide a source of power that can be leveraged effectively in that direction.

Has fundraising been important to your SCI journey?

Fundraising with Help Hope Live has been, full stop, a lifesaver.

In the earliest days of my relationship with the organization, it was helpful as one more piece coming into place in support of a full mandala of understanding about my new condition. More recently, and just before the pandemic, I went through a period where things looked as bleak to me as they had ever appeared. The relationship with Help Hope Live was a cornerstone of possibility.

During a year in which I miraculously survived, at an expense of over $200,000, the $50,000 raised in my honor with Help Hope Live made all the difference in the world. I cannot conceive of where I would have been without it.

Even under the weight of financial stress, my life is a source of gratitude and well-being. Through fundraising, I am raising as much a sense of relationship as finances.

In your view, where does caregiving and community intersect?

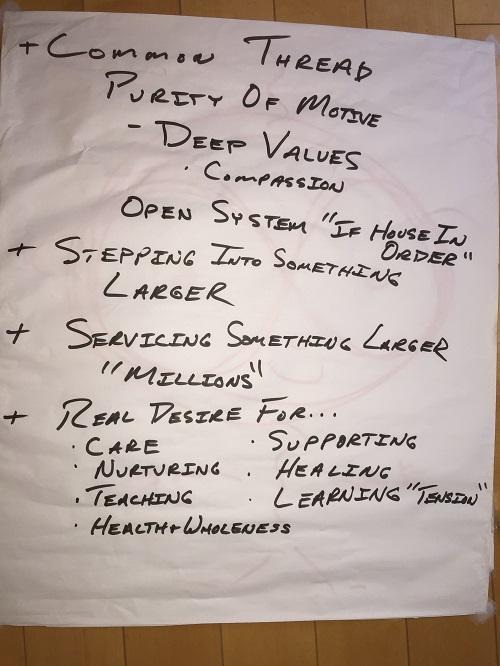

Research has shown that when an individual has a sense of purpose in their life, a vast range of markers for well-being go up. Purpose, a “why,” can be a profound aspect of our life’s journey – growing, touching others, and increasing the depths of our appreciation, love, and compassion.

The act of care is fundamentally a movement of service. I imagine an individual not simply coming to service the deadweight of my flesh, but rather to fundamentally participate with my intentions: to diminish the harm that I do, and to increase the well-being that I offer and that I seek to nurture in the world at large.

For me as a patient, caregiving can be not just the industrial acts of taking away gross suffering and increasing physical independence. Caregiving can be participation in a larger vision of life.

Caring itself is implicitly an act of community. Intention, service, and well-being all emerge in context. My work with MettaCare is an intention to nurture our global community and ourselves to enter a greater maturity of care. The essence of care must blossom and bloom to a much greater degree if we want what we know as “community” to flourish in these times.

What does hope mean to you?

Hope is an emotion – a longing for something. Hope fills our field of awareness. Hope is a prayer.

Hope is the emotion into which we pour our intention. What is our purpose? What is our “why”?

At our very best, what is it that we see in ourselves, in the world around us, and in those we love?

What advice would you give to a newly injured individual?

For me, the question is, how can we pick out the important signals in the cacophony of noise that makes up the profoundly unsettling new context of life with SCI – even affecting the concept of self for some? In my experience, most people in this situation are listening frantically. A deluge of information, from formal and official to informal and unofficial sources, is pouring in from every direction.

My advice goes out not so much to the newly injured individual but rather to those of us who are, and hopefully will remain, their community.

Take it slow.

Listen closely.

Feel deeply.

Consider carefully.

Learn. Think ahead.

Nurture your relationships.

Care for yourself.

Care for your community.

Catastrophic injury is a rebirth of sorts. So much changes that it is not unfair to label it “everything.” As in the case of any birth, in the care of a new mother, father, or infant, it is the surrounding community that makes all the difference in the world.

We can drink in the nutrients of each new moment, letting it nourish and change us so that we may become stronger – so that we may become wiser, and our service more integrated to the well-being of our entire community.

Written by Emily Progin

Written by Emily Progin