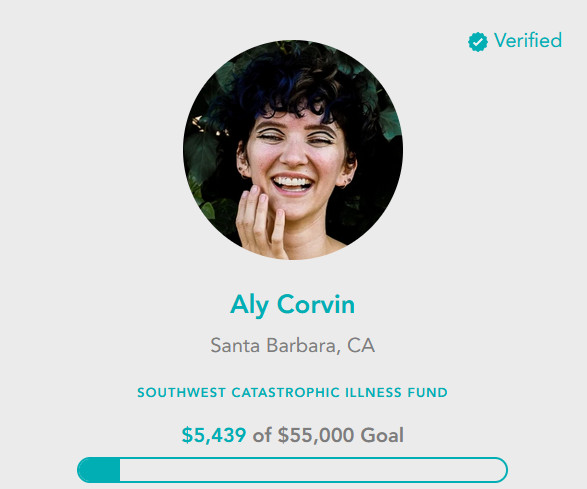

28-year-old Aly Corvin, aka Ms. Wheelchair California 2025, is a dancer and disability advocate living with multiple rare diagnoses that impact her body and mobility.

Fighting through misdiagnoses, discrimination, medical emergencies, and financial burdens, Aly returned to dance in 2024, but then a traumatic brain injury changed everything.

As she continues to fundraise with Help Hope Live to bring life-changing care and equipment within reach, we asked Aly to share her honest insights about disability, dance, ableism, fundraising, pride, and hope.

Let me tell you a story…

Imagine that you’re buying a house and the pipes are all leaking, the foundation is split, and the roof is half missing.

You tell your friends about it, and they say, “Yeah, owning a home is hard! We all have struggles!”

You start to believe what you’re experiencing is normal.

You finally fix the leaking pipe. Then the floor starts to cave in. Your friends say, “You know, I really think you just complain too much. Try being grateful for what you have.”

So, you do. You learn to love your sagging floors, peeling paint, and underwhelming décor.

Then one day, you walk by a friend’s house. That house is practically perfect. It has crown molding, vaulted ceilings, strong foundations, and paint that’s so flawless, it shines.

You start to understand the difference between what they think is normal and what you know is your reality.

That’s my experience living with these diagnoses.

My Fight for Answers

Living with medical unknowns and having to fight for a diagnosis is extremely unnerving.

It leaves you in a constant battle with yourself, not knowing if you should trust the signals your body is sending you or the professionals reading the data.

It’s one of the largest internal battles I’ve ever faced, and it has left me with permanent trauma that results in never knowing if I should trust my pain and symptoms in an emergency and go to the ER or if the ER will just label me as over-dramatic. My body seems built for disaster.

I dealt with a lot of challenges on the road to diagnosis. It would take me all day to list all of them.

I’ve experienced daily hip dislocations for as long as I can remember—injuries that a chiropractor once praised as a sign of being very flexible. He told my mom to be grateful because I’d be a great contortionist one day.

I used to fall asleep at the wheel after I got my license, and it still took 7 years to get diagnosed with narcolepsy. I thought everyone “slept” for a few seconds at a time, and that they were just better at hiding it than I was.

I cannot remember a single day that I haven’t had some sort of headache or migraine.

Some of the most difficult symptoms I live with are the ones that come and go, from heart palpitations and AFIB to hypothermia symptoms, heatstroke, extreme nausea, stomach cramping, GI tract issues, difficulty swallowing, amnesia, sharp pains in my chest, and much more, all without a solid reason why.

Grief is the hardest symptom. Grieving the function I have lost is so unbelievably frustrating.

I have several genetic red flags on my tests but not enough money to pay a doctor to read them.

Having a proper diagnosis will mean that I don’t have to go through life feeling like I ever have to compare my leaky, creaky house to someone else’s decorative sconces and perfect driveway. It will give me more of the full picture.

It will allow me to feel empowered to care for the body I was given with care, patience, and respect—not compare it to anyone else’s.

Pushing My Limits Over the Line

I have experienced several concussions in my lifetime from abuse, neglect, and growing up as a daredevil, but I have also experienced a frontal-lobe TBI.

Before my TBI, I had just worked my body up to a point where I no longer needed my wheelchair for activities like going to the grocery store or dancing on stage. I was only using the wheelchair for injury recovery and going to events that would require hours of walking.

At the time, I was homeless and not able to seek proper care. Because I live in a body that is hard to trust, I thought I was just having poor symptom days as I experienced muscle spasms, memory loss, dexterity and balance issues, and other things I can’t even remember. (Ha ..my TBI thinks that’s a hilarious joke.)

After the TBI, I began to experience such a decline in my overall health that I could no longer go anywhere without bringing my wheelchair along for the ride (pun intended). That persists today. You can imagine the toll this has taken on my mental health.

I’m a stubborn person, and I was taught that the only way I’d ever “get better” was to push the limits of what my body can handle, to build muscle that would hold my joints together.

Now, the harder I push my body, the worse I get.

I no longer constantly wish for a life without my wheelchair. I’m trying to be okay with it, one day at a time.

My wheelchair may be a symbol of something I’ve lost, but it is also my freedom.

However, it’s a lot harder to be excited about that freedom when so much of society and even the medical system view it as a way for me to “remain lazy” or “stay broken.”

Ableism, Stigmas, and Throwing Out the Rulebook

People don’t want to hear that someone who looks perfectly healthy can be as unwell as I am. It tells their unconscious mind that they, too, could suffer in silence one day.

I encounter discrimination and ableism every single day of my life.

It’s nobody’s fault for being uneducated, but if you turn down that education and choose to be unkind and not understanding, you are what’s wrong with the way society treats disabled people.

People would rather believe that I am dramatic, unable to handle everyday life, or weak. My resilience couldn’t possibly be this persistent. I must just want attention or want things handed to me.

I get it: that narrative is easier to swallow than the truth.

I believe that information combats the stigma that disability holds, so I like to share my story as much as I can so that those who relate to it can feel less alone—and those who can’t relate to it can form some kind of understanding.

If people don’t have that understanding, they cannot sympathize or grasp life with disabilities. I love speaking to children especially: kids aren’t afraid to ask what adults are taught to whisper about.

When kids are given the freedom to be curious, it leads to more compassionate and kind adults.

Kids can benefit from speaking to the disability community because we can teach them to be kind to their body while not giving up the drive to chase what you want in life.

I love doing things that society tells us disabled people are unable to do.

I thrive on it. There is no rulebook for this life.

It’s true that it opens the door for people to point their fingers and say, “Ha! I knew it: you’re not really disabled!” But more importantly, it opens the minds of other disabled people to see possibilities and opportunities they may never have dreamed could be within reach.

That right there makes it worth it to me.

Why I Dance and the Art of Movement

Dance has always been a part of my life. My mom says she can’t remember a time when I wasn’t wiggling.

Coming from a rough childhood, dance classes gave me structure, something to work toward, and a way to get out my energy. I fell in love with dance, but a few classes after I started dancing, the payments became out of my family’s reach.

I began to teach myself to dance in the style of hip-hop, which was the only style of dance I could do in my room.

For years, I watched YouTube videos of contemporary dancers. I took my first contemporary dance class at cheer camp during my freshman year of high school.

Flash-forward to college and I was completely swallowed up by the Fresno City College Dance Department. I was in love. Just 2 years into college, I was dancing professionally.

When my disabilities became too much to allow me to dance on my feet, I returned to the same college to re-learn how to dance in and with my wheelchair.

I was welcomed by my professor with open arms. I was invited back as a guest performer and choreographer, helping to educate our community on how captivating inclusive dance can be.

At first, despite having a place where I could train, I fought with the idea of dancing from my wheelchair. Some of this reluctance was due to grieving the body I once had. Some of it was not knowing how to navigate life feeling so much resistance against me.

When I got my first wheelchair, I began to lose the people I loved.

Drama queen. Attention seeker. Selfish. Needy. Difficult. Too much. You name it—it was said to me.

When I couldn’t even be accepted for who I was with my wheelchair, how was I supposed to want to dance in it?

She will laugh when she reads this, but I usually quote my professor Cristal Tiscareno when I talk about inclusive dance. The first day I met her in my choreography class, she told our entire room of students something:

“While some of you may disagree with me, every one of you is a dancer. You don’t need to have special training, be able to do 12 grand jetés, or perform in a perfect kickline to be a dancer.”

She explained that dance is an art of movement. No one gets to decide for everyone what “good art” looks like.

Art is meant to evoke emotion, and that emotion doesn’t always need to be joy. Art can make people sad, angry, or uncomfortable. That’s the point.

As movers, no matter how much mobility we have, we are just trying to evoke emotions in ourselves and others. Skill shouldn’t be the first and last thing on our minds.

Art rewards differences and diversity. The viewer of that art should, too.

Normalizing Disability—Even for Myself

When I received my first diagnosis, I was constantly comparing myself to other people. “I can’t be disabled. Disabled people struggle way more than I do!” Or, “I can’t say I’m disabled. That’s disrespectful to the ACTUAL disability community!”

In 2021, I found myself lying on the living room floor alone, surrounded by scattered Olive Garden pasta leftovers.

I had gotten up, and my fatigue was so bad that I had hit the floor before I could make it to the fridge.

That’s when I realized I was one of those people I had tried so hard not to group myself with.

When I was growing up, I happened to be surrounded by people who were disabled in some way. My best friend had one arm. My grandfather lived with paralysis from the neck down in the middle of our home.

Disability was normalized to me at a young age, but that’s not true for most people.

If we stop slamming the door in disabled people’s faces, we all may be shocked at what we can accomplish. Never assume someone is incapable of something. Ever. Everyone has their own pace of learning, and patience goes a long way.

As humans, our bodies are meant to move. We breathe, blink, and have beating hearts, all of which moves our body in some way. Allowing ourselves to explore all types of movement also allows our minds to expand.

My advice to others is that whenever you try something new, listen to your own body. Feel what it’s like to move in that way. Don’t think about what anyone else might think of you. That’s a waste. Chances are, they are more worried about being judged themselves than they are about judging you.

Maybe sports and dance aren’t your thing, but you thrive playing video games or engaging in online communities. Adventure isn’t black-and-white. Just get out there and try it.

The better we understand ourselves and our bodies, the better chance we have at understanding others and building a more understanding society.

Social media is doing so much good for visibility in the disability community. The reality is that most disabled people can’t leave the house as often as they would like, and that results in very little exposure for able-bodied people to see their perspectives.

We now have access to digital and social ways to share our untold stories.

We can create a world in which these things become normal. Social media is also an amazing tool for people who are curious and have the capacity to learn, whatever their reason for doing so may be.

The Life I Have, and the Life I Chose

I’m convinced that everyone who has risen to success has seen rock bottom.

This life can be exhausting, but I have chosen to live my life to the fullest while I wait for this universe to throw me a bone. If I do get effective treatment, or definitive testing and answers, I will celebrate that day when it comes.

If it doesn’t, I will still die happy and doing what I love.

I refuse for my trauma and life struggles up to this point to become my entire story. Instead, my stubbornness drives me to write chapters in which things start to look up for me, where I get to live the life that I’ve wished for myself while helping others along the way.

No matter who you are, life is about accommodations and specifications.

Helping other people to avoid what I’ve been through is my motivating factor every single day.

My title as Ms. Wheelchair California has given me more opportunities to connect with people from all walks of life, educating them on different types of disabilities.

I attended the Rollettes Experience 2024. They had booths set up with vendors, and one super-cute booth was titled, “Ms. Wheelchair California.”

When I asked if they had social media, I didn’t totally hear their reply, but they pointed towards a QR code. As I scanned it, I thought I was signing up for a newsletter.

Little did I know that I had just signed up with interest in competing in Ms. Wheelchair California!

A few months later, in a sea of emails, I found the organization’s California state coordinator reaching out to me with a formal application.

I was hesitant at first, but after some questions and a lot of reassuring answers, I agreed. That began my journey.

There are so many parts of my story, and stories like mine, that people don’t ever hear about.

I have been volunteering, fundraising, and giving my all to other people for my entire life. Somewhere deep down, my inner self wishes someone would notice when I need help and just help.

While I never expect anything in return, there’s always that little voice in the back of my head that sounds like my grandma. That voice is saying, “Sweetheart, just keep being your kind self and helping others. One day, someone will do the same for you! What goes around comes around, honey.”

It’s nobody’s job to notice me or reach out to me, but I will always have that small hope that one day, someone will do for me what I have offered to so many.

All I really want is what all of us want: to be seen.

I know my younger self would have had an easier time accepting my reality if I had examples to look up to.

The Ms. Wheelchair California Leadership Institute (MWCA) and Ms. Wheelchair America (MWA) are nonprofits that have given me the microphone I have been looking for.

Never did I expect to be seen as a public figure, but now that I am here, I couldn’t have wished for anything else.

Why I Started Fundraising…Again

Ms. Wheelchair California 2024 was the person who told me about Help Hope Live. She suggested that I start a fundraiser of my own, and though I was hesitant, by the time I met more of the team at Abilities Expo Los Angeles, I was convinced.

I have struggled financially my entire life. When I moved out at 18, all I wanted was to work hard and build up a savings of $10,000. I felt if I did that, I would be able to say I had “made it.”

As that dream was becoming a reality, thanks to me working 45 to 72 hours per week for longer than I like to admit, the pandemic hit. Three months in, I had to stop working.

I received temporary disability for about a year, but I was denied permanent benefits due to my “ability to recover”…an idea that my doctors greatly disagreed with.

From then on, the struggle has never really ended.

I blew through my savings while forcing myself to do odd jobs for rent money. As I fell behind on bills, my health suffered for it. I moved in with my fiancé to save some cash, but ultimately that resulted in us couch-hopping our way to homelessness.

Along the way, I had to deal with lack of transportation to doctor appointments, and even those appointments often came with skepticism. At times I was treated like someone who was only there to manipulate the system.

The benefits system is set up in a way that makes the cracks hard to see yet still large enough to swallow you whole.

My fiancé and I have made the decision to use what we have to make a difference in this world. Instead of using every penny to try to support my health—and never having enough for that goal to be sustainable—we want to spread awareness and try to just enjoy our lives the way they are.

It took a lot for me to agree to start fundraising.

I had an online crowdfunding page before, but it led to rumors about legitimacy and a lack of interest in donating to a cause that seemed “helpless.”

It was heart-wrenching, and it still haunts me to this day. I didn’t want to witness others thinking that I was trying to take advantage or get “free money” from them. I didn’t want to have another fundraiser ever again.

I didn’t want to have another fundraiser ever again. That changed with Help Hope Live.

I learned that Help Hope Live was a nonprofit that helped people like me raise money specifically for medical and related needs. I knew people would have a guarantee that the money was going toward verified expenses.

The tax deductibility for donors and the guidance from the incredible team were additional big reasons why I chose Help Hope Live.

Reaching my fundraising goal will mean getting the tools I need to seek proper genetic counseling, medical testing, and treatment options. I will be able to address the everyday things I struggle with, from an accessible living situation to repairs to my accessible van.

If these things are in my future, they will completely turn my life around.

Having access to reliable health care would literally add years to my life while increasing my quality of life profoundly. As a result, I would be able to continue my advocacy work and reach farther and wider than I ever have before.

What Hope Means to Me…and You

Hope is what I have to hold onto.

Hope that I can make a difference. Hope that the younger disabled generation will have a brighter and more accessible future. Hope that our society starts to wake up to the reality that everyone will one day become disabled if they are lucky enough to live that long.

I have hope that one day, I will have the opportunity to be financially independent, live in an accessible space, and live without the worry that it will all be taken away.

All I can do is hope.

When I look back at the past decade of my life, I’m proud I made it through homelessness with a smile on my face. With a not-so-great mental health past, I have been able to keep an optimistic outlook on life.

At this point in time, I’m not sure that there is much that can tear me down. To me, that is something to be proud of.

If you’re reading this, choose to be proud of who you are, regardless of what other people think.

I promise you that it will change the walk you walk (or roll) through this life.

Make a donation in Aly’s honor at helphopelive.org. Follow Aly on Facebook @alycorvin and on Instagram @aly.corvin and @mswheelchairca2025.

Reach out to her via DM or email her if you are looking for your next guest appearance or keynote speaker.