“Congratulations!”

Tears of joy falling from the eyes of family members and friends.

“She is doing great!”

Proud smiles.

I put on a brave face when people call me an inspiration, a miracle, the strongest person they know. Along with the victories I’ve experienced, I grieve a loss that few understand.

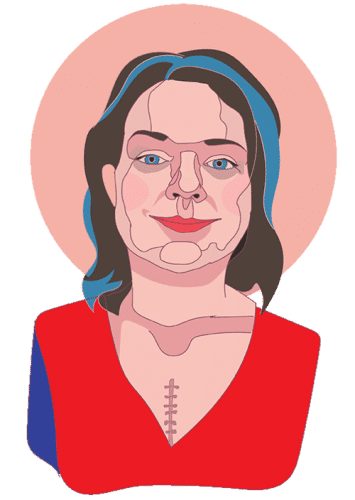

Most people go through life without ever having open heart surgery. I had two of these surgeries in 18 months. I stared in the face of death twice and lived to tell about it. Am I physically better? Absolutely. Am I healthy? No. Am I, and is my life, returning to normal? I am still trying to define that “normal,” and it almost changes daily.

The Mind of a Transplant Survivor

Part of my healing process that I’m currently addressing is to forgive myself—forgive my body and my heart for failing. This is not an easy task, but I chip away at it everyday. Transplant is a form of treatment, not a cure. A cure that is keeping me alive and out of the hospital but like all forms of treatment, there are side effects. There are also things that need to be done on a daily basis to keep this treatment working. Despite my best efforts, I do not know how long this heart will last or if another transplant is in my future.

The thought of needing a third open heart surgery often brings me to tears. It is my reality.

People are amazed when I tell my transplant story. I went from living a normal, healthy life to being placed on the transplant list two months later. Talk about life coming at you fast! Recovery has many ups and downs and the road is bumpy and filled with potholes. Still, each day provides an opportunity to find the gold and highlight the ups. When I do express the challenges, people often cut me off with clichés like, “Well, it beats the alternative!”

Sure, being a transplant survivor beats being dead, but those comments diminish my feelings. I sometimes keep things hidden to protect myself.

My friend started a Facebook Group for me when I first got sick where I could post updates from my hospital room. I was careful with my wording. There were times when I was scared, in pain, nights when I got no more than fifteen minutes of sleep. I would use the words, “I am uncomfortable today.”

How would people respond if I wrote my reality? “The pharmacy isn’t sending pain meds. I am in so much pain all I can do is cry and try not to breathe too heavily, and try not to cry, because that hurts, too. I loathe my breathing tube.” I kept those feelings between myself, the medical staff, and my visitors within those 24 hours after transplant. My eyes couldn’t even open but my mind was sharp. I remember those who came to visit for the allowed 10 minutes, those who held my hand and said encouraging things when all I could do was squeeze their hand back.

I had high expectations for what life would be like post-transplant. Reality often falls short of my expectations. I have not gotten my energy back, a bitter lesson when I attempted to return to work. The social aspect of my life took a blow as a result: I was a teacher, used to spending my entire day engaging with others. Today, I barely have the energy to spend time with my friends. By 8 p.m., without fail, I am in my pjs and hunkered down for the night.

Bridging the Gap Between “Us” and “Them”

I believe only heart transplant recipients understand each other fully. We are a small group, and we provide support for each other whenever we can. When I am struggling, I reach out to those I have developed relationships with over the past few years and they do the same in return. They get it.

I think I am trying to protect my family and friends from my experience—and protect myself from their reactions. They want to empathize, but it’s hard to empathize with something that is so difficult to explain. One of my closest friends explained she, at times, tries to put herself in my shoes, but it upsets her so much, she soon thinks about something else.

It hurts to know this reality is too much for people. At the same time, I don’t want to cause pain to others with my challenges. It is the life I am living and I am managing the obstacles the best way I can. I don’t want my loved ones to imagine being in my shoes. It is too much.

A medical crisis is always isolating. This is something I often discuss with my transplant therapist. I am aware that as I continue to turn inward, I run the risk of becoming more disconnected. This is something that is also common with my heart brothers and sisters. We can hear what someone is saying, but we aren’t always there.

Sadness and grief can pop up at any moment and those feelings do not always have a safe place to land. Many of my friends have been on the receiving end of meltdowns as I lash out or get angry over little things. I have yet to master controlling those outbursts and they have, unfortunately, put a stress on some of my relationships. I do have a great support system and they are always quick to forgive, and for that I am grateful.

My wish? That family and friends would listen—simply listen.

Don’t try to fix what cannot be fixed.

Don’t offer medical advice when I have a team of doctors a phone call away.

Don’t insult me by implying I’m handling this journey the wrong way.

Don’t compare your own medical troubles to a transplant—there is no comparison.

Just listen.

I know how hard you are trying, but I would love, love, love it if you listened and let me cry without getting uncomfortable. Know that I am not crying for myself today but for the Linda who was lost in this process. The one who is unable to return.

My Fears, My Hopes, My Truth

My biggest concerns are the new heart failing or my body rejecting it. I am on the young side when it comes to new hearts. There is a good chance I will need another heart, if I qualify for a second transplant. Because of that, I focus as much as I can on protecting the heart and staying healthy.

I am worried about my kidneys—between surgeries and living on an LVAD, they took a beating. Anti-rejection meds cause skin sensitivity, and I can get sunburnt even on a rainy day with 30 SPF on. Another anti-rejection med causes “toxicity in the brain.” I don’t know what that will mean for me in 10 years, if I make it to 10 years. Life is very fragile.

Despite all of this, today I realized something. If I need another heart, I will have to—and I will—do it all again. Yesterday I was feeling down, and I made the decision that if I got sick again, I would not seek additional treatment. But being alive and living each day to the fullest is important. I am here to soak up as much of this life as I can.

I am alive. I did survive. I have goals. I have hope.

My name is Linda Jara and I received a heart transplant on September 22, 2016. This is the me you don’t see.

Linda fundraises at helphopelive.org and manages the Facebook support group #IWearRedForLindaJara.

Written by Emily Progin