“How do you do resilience well?”

That’s the question John Berg posed to us, and himself, as he shared his reflections for this blog post about life after injury.

The father of our client Thomas Berg, John’s titles tell you a little about his story—M.Ed., CRC, ABVE/Diplomate, IPEC—but following a March 2023 accident, that story gained unexpected new chapters that are still being written today.

In this blog post, John shares with us the emotional reality of his son’s spinal cord injury, the financial and psychological challenges that persist 2 years after that life-changing day, and how a crisis can reveal true colors, deep generosity, and unexpected teachers.

Resilience in a New Reality: Life After Injury with John Berg

It was around 11:30 p.m. on March 11, 2023, when my wife and I got the call that would change our lives.

Our son, Thomas, had sustained a paralyzing spinal cord injury in a freak accident. A 500-pound cement cylinder fell on his head and neck, jamming his jaw into his chest. It severed four molars as it broke his neck.

We were living in Baja Sur, Mexico, for 3-6 months out of the year, and Betty and I were on our first drive down the peninsula, taking in beautiful topography and geology. We had decided to drive back the next morning. Our vehicle was already loaded up.

Thomas had just transitioned out of a job in Seattle after college in Los Angeles and Santa Barbara, CA. He typically lived 1,300 miles away, and we were both always busy. He had come down to Mexico so that we could spend time together, and he ended up wanting to stay.

When we got the call, we went right to the ER.

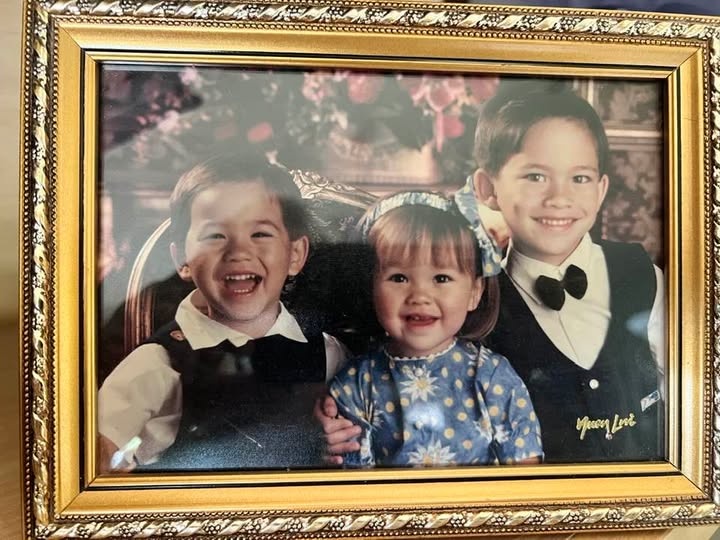

We called his siblings, Evan and Alison, and we told them that Thomas had sustained a spinal cord injury.

At the ER with Thomas, they had no MRI—just an X-ray—and no neurosurgeon. We had to airlift him out of Mexico with a Learjet from San Diego. By 2 a.m. on March 12, I was in the air with Thomas, a flight nurse, and a pilot.

That flight cost $40,000 in advance. I had to use two credit cards to pay for it.

He received spinal fusion stabilizing treatment from C2-T2 levels in San Diego at Hillcrest Hospital, then transferred to inpatient rehabilitation in Seattle in June 2023.

His medical services over these past 2 years have included spine and urological surgeries and invasive medical treatments, including a G-tube to feed—he could not eat or drink for several months. High C-level fractures often remove the basic ability to swallow liquids or foods.

Thomas existed in frustrated silence with a ventilator for oxygen support and tube feeding.

He finally made a transition back home, but his rehabilitation goals were altered by an unexpected and isolating diagnosis.

How did you and Betty react to this life-changing moment?

For me, it was a warrior mentality. We had to make clear, decisive decisions.

There was no time to scramble around—his life hung in the balance.

Prior to this injury, none of us had experienced any serious injuries or illnesses—just normal issues related to aging for us and our 3 kids, who were in their 30s.

It was a complete shock, seeing paralysis occur and knowing the potential severity of this kind of injury.

I went into a state of hyperfocus on priorities. What needs to be done? How fast do we need to do it? Which options do we have?

I made all of the decisions. Betty was like a stunned animal, hardly able to make decisions or react as things unfolded.

No guidebook exists to explain and recommend action plans after this kind of life-changing injury.

Evan and Alison made plans to come down. I rented an apartment for several months near Thomas’ treatment center.

For months, I was at the hospital every day.

I learned everything about what Thomas’ team needed to do for care, treatment, medication management, tracheotomies, oxygen saturation, intubation, prescription management, and wound care. I learned and observed in-person what speech therapists do to test for swallow function.

Looking back, I felt like a graduate student, learning something every single day to help get care for Thomas.

I tried to lean on my knowledge of the concept of resilience. How does someone engage in life to create resilience? How do you do resilience well?

I was eating right, getting exercise. Music was always important to me, a core method of personal expression and a source of pleasure and social connection for me to my “tribe.” So, I brought my guitar, and I found a place near the apartment where I could play. I kept a diary on my computer daily, processing thoughts and emotions.

I kept it objective, avoiding falling into a victim role.

In addition to the intensive care and treatment that Thomas required, there were so many ancillary considerations.

Thomas had 2 dogs—he had just adopted a puppy 5 weeks before his injury. The pets couldn’t just hop a plane back to the U.S. Betty needed to stay in the condo in Mexico to arrange for veterinary care and appointments, working to get the dogs clearance and tickets back.

Betty didn’t even see Thomas regularly for those first few weeks. I think she needed the time just to process how all our lives had changed.

It also fell to her to take care of normal business demands and new issues with this new life.

We had decided we were going to move Thomas to a spinal cord injury program in Seattle once he was stabilized in San Diego—he could not travel for 6 months without a registered nurse at his side.

Unfortunately, that’s when he sustained a fungal disorder of the skin called Candida auris. He likely picked it up from a patient he was hospitalized with.

The condition is asymptomatic but contagious, so it requires the use of intensive PPE (personal protective equipment) for every therapist, physician, and visitor. There is no cure and no prescription to treat the fungus, and it can kill a patient with a compromised immune system.

That diagnosis put our program plans on hold.

Our home began to look like a clinic, full of various supplies I was not familiar with before this injury took place.

Around-the-clock care and constant advocacy simply became a reality in our lives. Many of the days in our first year after injury were semi-controlled chaos. Medical stability is not a part of life with paralysis, and every week was full of appointments and medical care.

How has your family been affected financially by this injury?

Out-of-pocket costs have become a routine part of our lives.

We live 8 miles from downtown Seattle, so if needed, we could call 911 and get emergency transport. But if we were anywhere else without a wheelchair van, we’d struggle to get Thomas emergency care if he needed it.

Public services are not always safe, convenient, or reliable, and insurance doesn’t cover what you require to keep a loved one safe, especially in an emergency. A wheelchair van is a needed cost that insurance won’t cover. Even a used wheelchair van cost us $40,000. Without one, scheduling, showing up on time, and making important medical appointments are compromised.

Isn’t transportation part of life with a disability, and therefore part of the reason why we have insurance?

At home, we had significant home modifications to make to accommodate the reality of life after injury. A contractor put in a ramp system and a widened cement sidewalk with a safety railing. Our multi-story home needed room conversions and a full bathroom renovation to create a flat-floor shower Thomas could use.

That shower renovation alone was $20,000 or more out of pocket.

The only bed that insurance would cover—which Thomas would spend most of every day in—didn’t fit him at all. It looked like a small bed made for a Scout cabin. Thomas is 6’1” and was down to 125 pounds while on his feeding tube, but he’s now 180 pounds.

That bed—a critical need—was another out-of-pocket expense we had to take on just to meet his basic health and safety needs.

The injury also left Thomas with the need for dental repairs as the weight of a cement pole crashed his head and jaw into his chest, fracturing his teeth. These were out-of-pocket repairs at $1,100 to $1,200 per tooth.

Caregiving is an ongoing need that is almost impossible to meet fully without investing $120,000+ per year out of pocket. Lifetime costs for caregiving for someone injured at age 34 can exceed $3 million to $4 million.

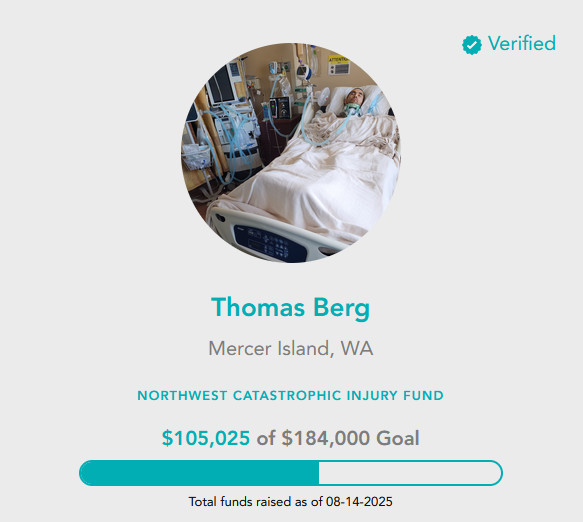

How did you find Help Hope Live?

We found Help Hope Live a month after Thomas’ injury at the recommendation of one of his best friends, Colin Buchanan, who was paralyzed at age 16. Colin had finished a BA degree in Chicago before relocating to a warmer climate—10 minutes from the hospital in San Diego where Thomas was.

We welcomed the serendipity.

Colin came over every few days to see Thomas. Now 36, Colin works part-time in medical device sales and has a vehicle, a dog, and a downtown apartment, so Thomas had that exposure to life after paralysis even before his own injury.

We liked that Help Hope Live would help protect Thomas’ eligibility for Medicaid, and we liked that it was a 501(c)(3) that would offer benefits to donors, including tax deductibility for donations.

I am well-known professionally, and I have held seminars periodically in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico in addition to contributing to studies, publications, and articles across groups with thousands of members.

Tapping into that career network has been a key part of our fundraising efforts. We’ve been able to reach people with the power to broadcast this need—organizations published an article about me and my son, which drove donations.

My estimate is that my colleagues made up 80% of all donations in Thomas’ honor.

Through Thomas’ Help Hope Live Campaign Page, updating our community about his health became part of my resilience.

Participating in writing and communication can give you perspective and balance—it’s important to chart a diary of your life. For me, writing is therapeutic. I wrote a personal diary alongside the updates I wrote and shared for his community.

How is Thomas’ health and mobility today?

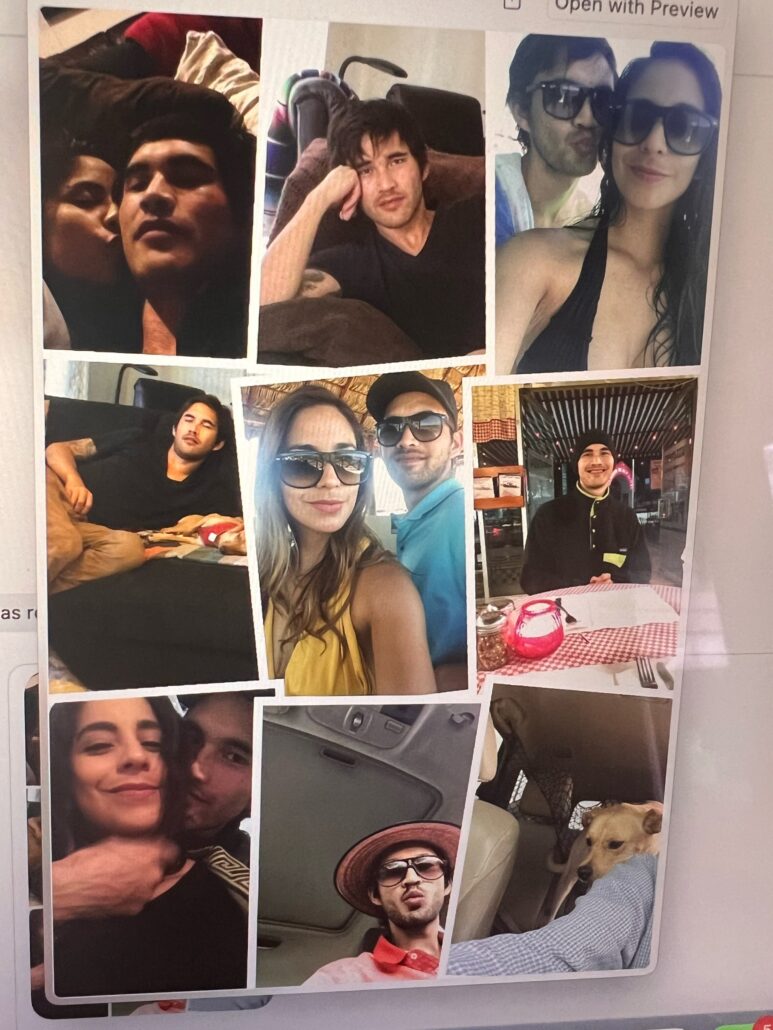

Today, Thomas has bicep function on both sides and enough movement in his left wrist to be able to use a power chair. He has no hand motion, no finger movement on either hand, no pinching, and no grasping.

Picture not being able to pull up a blanket if you’re cold, or being unable to feed yourself, brush your teeth, or hold a cup.

Thomas has a voice-activated bed with which he can elevate his own legs and head. He also has a voice-activated iPad so he can turn on the TV, watch YouTube, and make phone calls.

Due to his Candida auris diagnosis, Thomas is basically in isolation.

All human relationships tend to be based on sharing a mutual interest or event—we become friends because there’s something we share, from recreation to sports to music.

When you become a quad, especially with the level of medical isolation Thomas is facing, it’s a guaranteed level of loneliness.

Adjustment to this level of disability is the biggest barrier right now, and it’s a psychological barrier—adjusting to a profound disability is a major obstacle that all people handle differently through an individualized process.

We live in a society of beauty and athleticism. Especially in America, we admire strong, beautiful people. Thomas has to see himself differently now through those eyes.

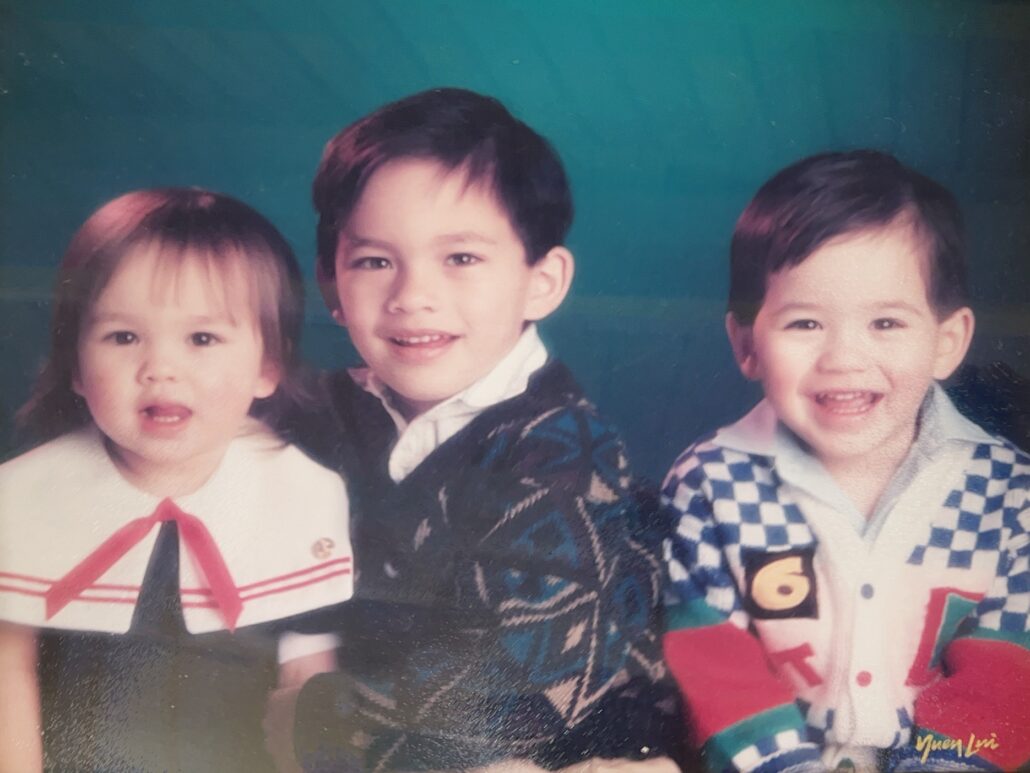

Thomas has been athletic and adventurous all his life. He started waterskiing at age 12 and took to it right away. Snowboarding, surfing, mountain biking, cliff jumping, international travel—all these things have been a part of his life along with education, work, and socializing.

His life is from the neck up right now. He is facing the need to reinvent himself and how he sees himself.

What impact has Thomas’ injury had on your family?

A spinal cord injury is a family affair, and it has an impact on everything.

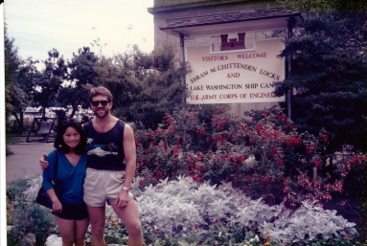

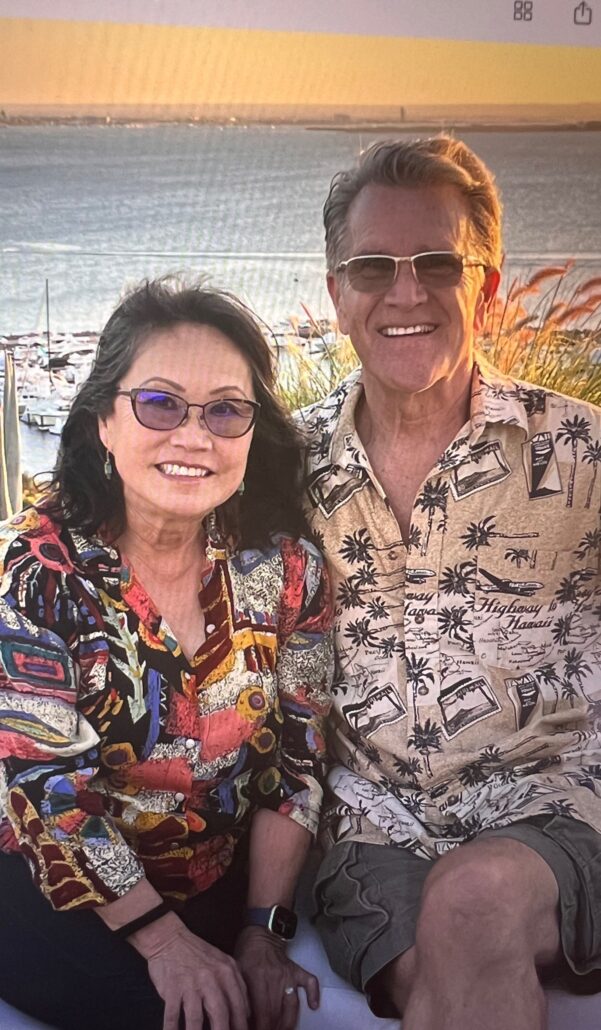

I’ve been with Betty for 43 years. We haven’t gone out for more than 2 or 3 hours since the injury—it’s difficult to find any residual energy after caring for Thomas to have any kind of normal life.

It’s an abnormal life. We haven’t had a “day off” in 2 years and 3 months so far.

Finding caregivers is not just a financial challenge but an administrative one. The Medicaid benefits that Thomas is eligible for don’t include a streamlined system for finding or screening caregivers. You have to sort through many applicants to find the right fit.

Most of the caregivers we can find have almost nothing in common with Thomas, which makes it difficult to maintain a strong caregiving relationship being around each other for 8 to 16 hours every day. Add that to the extra care precautions required by his Candida auris diagnosis and you can see why caregiving is a significant portion of life for Betty and me.

Thomas should be eligible for home health OT, PT, and nurse consulting or case management through his benefits. I have to keep asking insurance, over and over, to pay for these covered services.

I have asked, “Why can’t you refer us to someone for these covered services?”

The response is, “We can’t find anyone in your area.”

In a metropolitan downtown area? Close to 3 hospitals and 3 major universities offering degrees in these fields? The real reason is likely that these benefits offer a pay structure that is less than market value compared to a clinic or hospital.

Advocacy and negotiation are now a constant part of our family’s lives. We often feel like we are just spinning our wheels.

My mom lived to almost 103—a registered nurse who never had a surgery. All of a sudden, here I am with a new prostate cancer diagnosis myself and a quadriplegic son.

I’m almost 74 years old, and my wife is almost 69. Bending, stooping, lifting, and transferring to wheelchairs, a shower, a van—coupled with the daily emotional impact… Sometimes we look at each other and wonder how long we can really do this.

Grief never leaves or resolves entirely—perhaps it hibernates for short periods.

I was diagnosed with prostate cancer myself shortly after Thomas was injured. I had to go through radiation therapy while we continued to manage his health and care.

We retained an attorney, and we re-wrote our will and trust. While this fundraising campaign with Help Hope Live has saved us from gutting our financial preparedness for our own future as we age, we’ve still had to do financial and legal planning around this injury.

Ignoring financial issues at this stage could be ruinous—we could end up broke ourselves.

We know that realistically, Thomas may need to be a part of an adult caregiver home in the future. We are doing that homework now, while we can.

We have thought about seeing if we can take a rental property we own and turn it into a place he could safely live. I imagine a place with 3 SCI residents like Thomas, a live-in caregiver, and outsourced support. We’re looking for options to make this a financial reality for his future and ours.

What have you seen emerge in the people around you over these past 2 years?

It’s a Buddhist saying that “the lesson(s) we are learning are yet to reveal themselves fully…When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.”

I’ve become the student, and so many people around us have become the teachers, regardless of their age, background, and education.

This kind of life-changing event opens up new channels in your life. I’ve made unexpected connections with so many people in support groups. We’ve witnessed the thoughtful actions of so many people, many whom we have never met.

I’ve found that national and state-based support groups are important in your life plan if you’re supporting anyone with a spinal cord injury or other profound impairments.

And then there’s the generosity. One of my former employees donated $7,000.

People pop out of the woodwork when you least expect it. Others leave when you expect them to stay.

People reveal themselves and their value systems in times of crisis. A crisis reveals people’s value systems—it shows true colors.

How has this injury motivated you to mentor and assist other families?

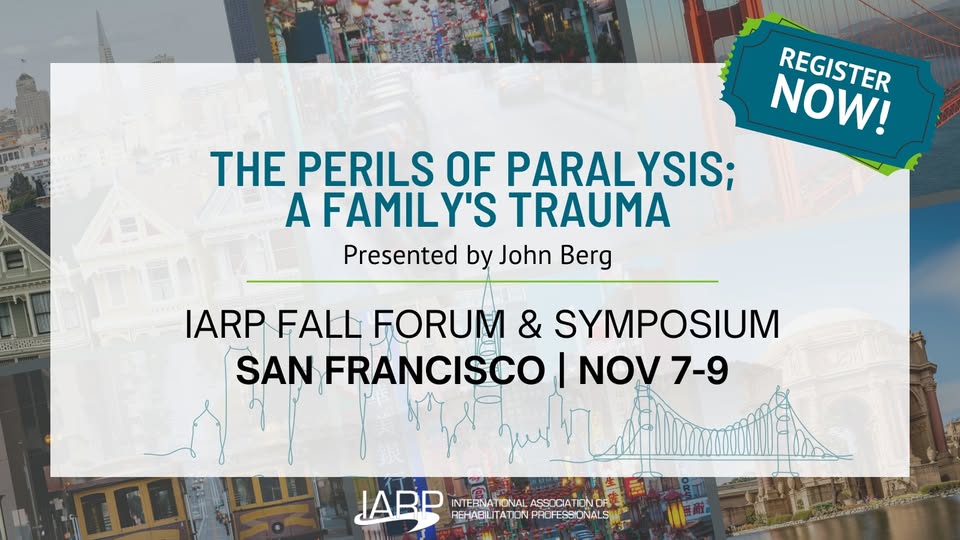

I’m a master’s-educated and board-certified vocational rehabilitation counselor, so I have worked with people with disabilities since 1981. Prior to Thomas’ injury, I had a lot of experience working with people with a wide range of diagnoses and injuries, primarily resulting from auto accidents, workplace injuries, or maritime injuries.

I had 23 employees and consulted with major corporations, primarily assisting people with disabilities in returning to work. I’ve also served as an expert witness for litigation cases.

Based on my experiences with Thomas over the past 2 years, I can now see that there is a huge gap in information about the impact of these kinds of injuries on the family. I could only find one published article in a peer-reviewed journal on the topic across all my research in this area—the author, a university professor in Texas, happened to be a quadriplegic himself.

Written details are scarce or non-existent on family impact and damages related to the domino effect that an injury can create.

There is a big deficit between the info that is out there and what family members need to know, from establishing support systems and finding caregivers to dealing with the out-of-pocket costs.

I had some experience with quadriplegics and paraplegics prior to this injury. But I thought, what about someone with ZERO experience? Where will they find what they need?

I was the keynote speaker in November at a national conference for life-care planners for injured individuals. I’ll be going to Denver in October to speak to a group of economic professionals about the true cost of living with a spinal cord injury, and I’ve been asked to speak at a conference in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in Spring 2026.

I feel like I have a new calling for myself: to find inspiration and educate others so they can avoid the pitfalls that a newly injured individual and their family may face.

A friend of mine with a son living with a similar injury said this to me:

Purpose finds us—even when we weren’t looking for anything like it.

Donate to Help Hope Live in honor of Thomas Berg at helphopelive.org.